Introduction

I had intended to write a blog post that would conclude with some examples of universally good architecture. Components which could be included in any building and BANG you’d have a great place.

A lego set, if you will, of good architecture.

Unfortunately, as I researched and discussed with better-informed people than myself, I realised such universal components do not exist. They do not exist because good buildings respond to their context and depend on technology available at its time. There cannot be a blueprint because there is no single answer. A good building in one location could be a terrible building in a different location.

What I have found instead are some key guiding principles. Not quite the easy answer I was searching for but, perhaps, more profound.

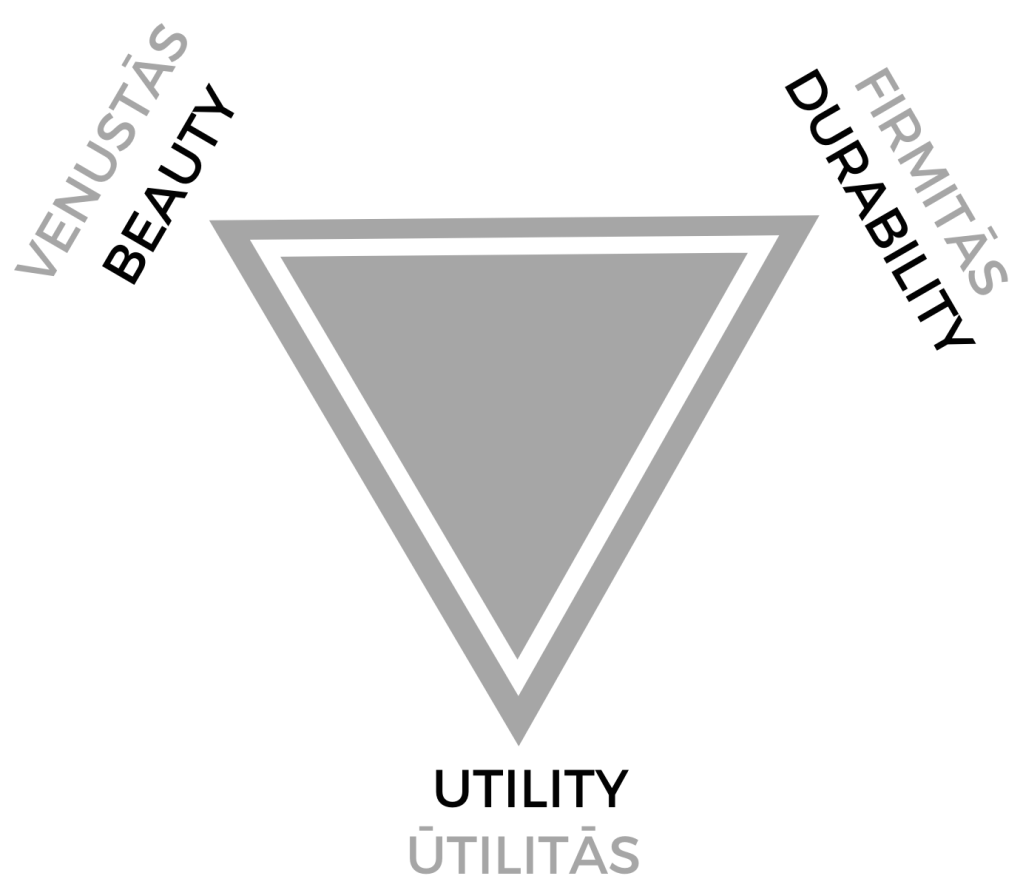

These are the principles of Vitruvius, the Roman architect and engineer. He specified that a good building had to be, in equal measure, durable, useful and beautiful.

It’s astounding that something written over 2,000 years ago could still be so relevant today, but then I suppose that’s the real test of a “truth”.

Why are there no prescriptive truths?

1. Context

In grey, cloudy London, we put a premium on light and space. A good building is one with big windows and high ceilings. Giving us a sense of light and space otherwise missing in this city. Contrast this with a traditional southern French farmhouse, often built with thick stone walls and small windows with the aim of keeping the farmhouse cool. When you want sunlight in the south of France, you go and sit outside.

At its most basic, a good building is one that protects us from whichever elements we have too much of and gives us more of what we’re missing. For example:

In the mountains – keep out the cold, keep in the warmth. In a desert – keep out the warmth, keep in the coolness. In bright places – maximise shade. In dark places – maximise light. At the top of a cliff – protect from the wind. By a river – keep water out. In arid places – keep the humidty in. And so on.

The only real thing that these have in common is shelter. Shelter from the dominant elements.

This is why it is so hard to build good, timeless places. It is because there is no one answer. Even the most basic purpose of providing shelter means different things across the globe.

2. Technology

Technology changes how we can build and therefore changes what constitues a good building. Take the courtyard for example.

Courtyards appear to have an eternal appeal, meeting at the intersection of indoor/outdoor and public/private. From Roman villas to Chinese Siheyuan to Morocan Riads there are so many pleasing examples of courtyards, I assumed courtyards were intrinsically good places that humans like to be in.

However, as building technology has allowed us to build taller buildings, floorplans need to change too.

For example, if a new building is built with the traditionally successful layout of the courtyard, but is then 15-storeys tall, the experience inside the modern courtyard is a world apart from those that have lasted for centuries.

Essential to the courtyard’s success are sunlight, skyviews and a breeze, all of which are lost when a courtyard is in the middle of a tall building. There are hundreds of examples across London alone of gloomy, damp courtyards which serve no purpose to anyone.

Technology has, of course, also enabled us to build structures of awe-inspiring grace and magnitude, with new building techniques and materials that have rendered previous beliefs about proportions in architecture irrelevant. Further providing that a universale recipe book for architecture cannot exist.

So if there are no prescriptive truths, no lego set for good architecture, what is there? Below I explore some of Vitruvius’s principles, words which have endured for over 2,000 years.

Vitruvius’s Truths

Background

Vitruvius was a Roman engineer and architect (interestingly the Romans did not make a distinction between the two), who wrote De Architectura (On Architecture) in c.15-30BC. It is the only full, surviving publication of Roman building.

De Architectura is a collection of 10 books detailing all elements of the built environment from Theatres to Gymnasiums to Sundials. Vitruvius wrote De Architectura for Emperor Augustus, having worked as an engineer and architect under his predecessor Julius Caesar, so Augustus could “become familiar with the characteristics of buildings already constructed and of those which will be built.” (Vitruvius, Schofield Translation, 2009, p.4).

Guiding Principles

Underpinning De Architectura is Vitruvius’s conviction that all buildings must be durable, useful and beautiful.

Durability will be catered for when the foundations have been sunk down to solid ground and the building materials carefully selected from the available resources without cutting corners;

The requirements of utility will be satisfied when the organistion of the spaces is correct, with no obstacles to their use, and they are suitably and conveniently orientated as each type requires.

Beauty will be achieved when the appearance of a building is pleasing and elegant and the commensurability of its components is correctly related to the system of models.

(Vitruvius, Schofield Translation, 2009, p.19)

Importantly, Vitruvius does not appear to favour one of these elements over the other. They are all crucial, like a three-legged stool, this theory does not stand up with only two parts.

As guiding principles, I’ve yet to hear better.

Even as new buzz words enter the world of real estate these three principles stay relevant.

Take “adaptability”. This is a type of durability. If a building is durable it should be able to adapt to change.

Or “sustainability”. If a building fulfills the principal of utility, it should be used in the most efficient way and therefore will not be wasteful.

Now on to beauty, undoubtly the most nebulous of the principles and often considered of secondary importance. However I believe Vitruvius was right – beauty is of equal importance. If you find the term beauty too subject, it’s worth noting that in some translations of Vitruvius, it is referred to as “delight”. This is, perhaps, an easier term to digest as a universal truth as delight indicates a generally positive response rather than an explicit belief in something being beautiful.

If a building is not beautiful (or delightful), it cannot be truly durable. Our human instinct to improve will tempt us to pull it down and replace, even if it is structually sound and still functioning. This has been the woeful fate of many 60s/70s/80s and 90s buildings in recent years and the wasteful cycle will continue if we do not insist on more attention to design.

Secondly, whilst it’s pretentious to claim that architecture can change our lives, it does have the power to uplift, inspire, energise or calm. Beauitful buildings may not be life-altering but they certainly can be life-enhancing. Surely, therefore, if we have the power to improve the backdrop to people’s daily lives, we also have the moral obligation to do so.

Whilst it is not quite the recipe book or lego set I was searching for, these truths are more profound, reflecting the true complexity of buildings. There is no doubt that any developer that considers these three guiding principles will be well on the way to making truly great buildings.

It is astounding and humbling to be reminded that, even with our technological advances, the underlying principles of creating good places for humans have not changed in 2,000 years.

And surely that is the closest we can get to a universal truth.